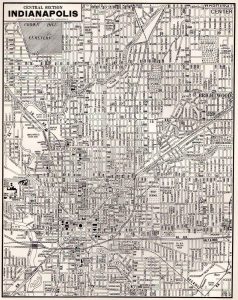

Here’s a map of Indianapolis.

While it might seem innocuous, note where the interstates are, and the color of the neighborhoods through which they run.

The map is a 1937 redlining map, outlining neighborhoods where white people and black people were allowed to buy houses. To be clear, the red areas were (and in most cases still are) majority black neighborhoods.

See how none of them go through the white neighborhoods, indicated by green and blue, even when it would’ve been a more direct or logical path for the interstate to take?

Look at Fountain Square. The South Split cuts it off from downtown almost entirely. Access to the neighborhood from the city is essentially only possible via one street. After the interstate, the neighborhood was decimated; formerly a working-class neighborhood of Black people, Fountain Square collapsed. It’s only recently become desirable again through the efforts of artists and community organizers. A similar story could be told about my own neighborhood of Windsor Park, or Martindale, Brightwood, anywhere on the Near East or South Side.

The interstates in Indianapolis were built in the mid-1970s, two decades after the civil rights movement began; eight years after the assassination of MLK and Robert F. Kennedy’s famous calming speech in what is now Kennedy-King Park (now also cut off from downtown by I-70). It wasn’t over then, and it isn’t over now. The biggest monument to racism in Indianapolis is a road specifically built through minority neighborhoods to allow white people to come downtown quickly and easily flee back to their suburbs without going through “dangerous” areas.

The interstates in Indianapolis were built in the mid-1970s, two decades after the civil rights movement began; eight years after the assassination of MLK and Robert F. Kennedy’s famous calming speech in what is now Kennedy-King Park (now also cut off from downtown by I-70). It wasn’t over then, and it isn’t over now. The biggest monument to racism in Indianapolis is a road specifically built through minority neighborhoods to allow white people to come downtown quickly and easily flee back to their suburbs without going through “dangerous” areas.

During his speech, Kennedy said, “What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness, but is love, and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black…the vast majority of white people and the vast majority of black people in this country want to live together, want to improve the quality of our life, and want justice for all human beings that abide in our land.”

We have so far to go.

Some might ask, “now what?” And I honestly think we should get rid of the interstates inside 465; but more immediately (and probably more helpfully) we should acknowledge how we white Indianapolis-ians have benefitted directly at the expense of Black residents so recently and work to see what systems exist in our city today that must be addressed if we are to truly live without division.

• • •

Sources: