So, here we are: the end of the year—and what a year it’s been.

If this is the first article you’ve seen in this series, I’ve been on a bit of a quest to learn about my own brain and the way it works; a quest that resulted in a prescription for ADHD medication and a great deal of self-reflection along the way (Want to see some of that journey? The full series is in the ADHD Category). Things have been going really well.

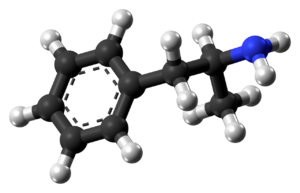

But first, my medication status. Since my last update in October, I’ve asked for a dosage increase from my doctor. During the consultation, I mentioned my concerns that the dosage felt insufficient as the days grew shorter, and he cautioned me to be on the lookout for seasonal depression (also known as Seasonal Affective Disorder). This is something I’ve had trouble with in the past, though it didn’t feel quite like that feeling of spiraling despair and gloominess that S.A.D. hangs over my head. In any case, he increased my dosage; I’ve now been taking the 12.5mg dosage of Adzenys XR-ODT for about two months.

But first, my medication status. Since my last update in October, I’ve asked for a dosage increase from my doctor. During the consultation, I mentioned my concerns that the dosage felt insufficient as the days grew shorter, and he cautioned me to be on the lookout for seasonal depression (also known as Seasonal Affective Disorder). This is something I’ve had trouble with in the past, though it didn’t feel quite like that feeling of spiraling despair and gloominess that S.A.D. hangs over my head. In any case, he increased my dosage; I’ve now been taking the 12.5mg dosage of Adzenys XR-ODT for about two months.

And it’s working amazingly well. Amid a project of increasing complexity at work, I’ve found myself to be able to commit executive function and focus to the tasks in a way that I’ve never been able to before. And with the Christmas season in the rear-view mirror, I can now see that the extreme whiplash of switching between contexts—from work, to kids, to kids’ school, to spouse, to friends, to shopping, to church, and back again—hasn’t caused the same level of executive paralysis or mood problems that it has in years past.

And it’s working amazingly well. Amid a project of increasing complexity at work, I’ve found myself to be able to commit executive function and focus to the tasks in a way that I’ve never been able to before. And with the Christmas season in the rear-view mirror, I can now see that the extreme whiplash of switching between contexts—from work, to kids, to kids’ school, to spouse, to friends, to shopping, to church, and back again—hasn’t caused the same level of executive paralysis or mood problems that it has in years past.

I measure the effectiveness of my treatment in the following realms: alertness, focus, motivation, executive function, energy levels, mood, temporal perception, memory, and cognition. And over the last two months, almost every category has seen massive improvement. Focus and executive function have seen the greatest improvement; the other categories have seen more modest (though still considerable) gains. Notably, in situations where I would ordinarily have written off an entire day as “just one I have to make it through”—that is to say, days in which I didn’t expect much if anything in the way of work done, usually due to poor sleep the night before—I’m actually surprised to find I am more alert and have higher energy levels than expected, and I’m able to put up some decent productivity.

The only category in which I haven’t seen a vast improvement is temporal perception; I’m regularly startled to discover that it’s after 2pm, and I haven’t eaten lunch yet, for instance. Interestingly, this is a bit of a regression for me, as that’s actually one of the first improvements I noticed about this medication months ago. I have a theory that in the past my lack of focus provided a check against time-blindness, and my focus improvement is now overriding those gains; but that’s a theory that I haven’t had a chance to interrogate or investigate at all. Still, of all the factors, my temporal perception is the easiest to build coping skills around, with techniques like Pomodoro or more strict schedules. I’ll be following up on the results of those experiments here in the future, if they’re interesting; perhaps even with a new series.

One thing I’ve discovered is that there’s a “virtuous circle” of focus: since my medication increase, my focus is such that I can regularly check off a task (or at least a significant chunk of one) nearly every single day, which provides a new feedback loop as my brain realizes that accomplishment is possible, leading to my being able to check off more tasks the following day.

This feedback loop, I’ve discovered, applies to motivation (motivation is a very transferable commodity within my brain), executive function (once I’ve started on a task, it becomes easier to start the next one), mood (calmer David in the morning usually leads to calmer David in the afternoon), and cognition (once I’ve begun creating heuristics and lenses through which to solve problems, creating them for other problems becomes simpler). I’m curious to discover if this also applies to alertness, energy levels, temporal perception, and memory; if so, this seems like a tool that I could use pretty effectively in the future for even more productivity.

This feedback loop, I’ve discovered, applies to motivation (motivation is a very transferable commodity within my brain), executive function (once I’ve started on a task, it becomes easier to start the next one), mood (calmer David in the morning usually leads to calmer David in the afternoon), and cognition (once I’ve begun creating heuristics and lenses through which to solve problems, creating them for other problems becomes simpler). I’m curious to discover if this also applies to alertness, energy levels, temporal perception, and memory; if so, this seems like a tool that I could use pretty effectively in the future for even more productivity.

And this isn’t the first time I’ve discovered such a tool that I can use “against myself,” to accomplish things or otherwise exceed my ordinary mental limitations. As CGP Grey and Myke Hurley of the Cortex Podcast describe it, within your mind is a “monkey brain” that insists upon redirecting your brain to the next shiny thing. The “monkey brain” has control of your dopamine (and other chemicals), which means that it is able to exert considerable influence over your conscious mind as well; simply trying to “push through” the monkey brain’s insistence that you simply move toward the next exciting thing can work for some people, and making the monkey brain do your bidding through logic or force of will works for others; but for most people (especially neurodivergent people), we should expect to make use of clever trickery and tomfoolery to get any work out of our monkey brain. I’m hopeful that this new feedback loop will be helpful in allowing me to be more productive.

If you’re one of the people who has found the saga of my fight against the monkey useful or interesting, I really appreciate your presence and well-wishes. Thank you so much for going on this quest with me. If it’s helpful to you, please let me know below. Next time, we’ll be talking about psychological evaluation and the process by which I have been pursuing an official diagnosis.

In any case, thanks for being with me on this journey this year. Happy New Year to you all, and here’s to knowing ourselves better in 2024!