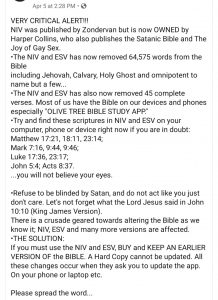

“Very critical alert!” These really scary images have been going around social media recently. “You can’t trust your Bible!” they implicitly (and in some cases explicitly) shout. “It’s being corrupted by—” well, that’s part of the problem. It’s unclear who’s supposed to have corrupted the Bible, but apparently it’s happened.

“Very critical alert!” These really scary images have been going around social media recently. “You can’t trust your Bible!” they implicitly (and in some cases explicitly) shout. “It’s being corrupted by—” well, that’s part of the problem. It’s unclear who’s supposed to have corrupted the Bible, but apparently it’s happened.

In actuality, it’s not actually worrying at all because it’s asking the wrong question. This is a very long post about how you can indeed trust your Bible. But before we deal with the question they should be asking, let’s consider what the NIV and other modern translations are trying to accomplish from omitting these verses, if that were indeed what happened.

The Inscrutable Agenda

- If they were trying to advance some gay agenda (as this meme spuriously implies), why wouldn’t they remove, for example, Romans 1:27? What do they gain from trying to throw doubt upon this teaching of Christ that is not only preached elsewhere, but attested to by His very life and death? What do they gain from removing a verse that speaks to His love and grace?

- So do these verses represent a core doctrine of the faith? Well, kind of. By which I mean, yes, but not exclusively; it’s also in Luke 19:10 and John 3:17. So if Zondervan was trying to change the Bible and remove some core element of doctrine, why would they leave it intact in two other places? Why just these two verses?

- Further, If they were trying to remove these verses from the Bible, why did they include it? That’s right, it’s actually there; in footnotes for this verse in almost every published version of the Bible, the “omitted” words are actually included verbatim.

In short, if they were trying to remove a concept from the Bible, they chose poorly and did a remarkably bad job of it. And they’ve continued to do a remarkably bad job of it for almost 50 years now, apparently, as the NIV has undergone multiple revisions and I can’t find evidence that any further verses have been “removed.”

The Shady Publisher

Now, let’s see about the claim that this is some ploy by a secular publisher. It’s true that the NIV is published by HarperCollins, but it’s untrue that it’s not published by Zondervan; in fact, Zondervan was acquired as a subsidiary of HarperCollins in 1988, and remains a separate but wholly owned entity of the parent company.

This may seem semantic, but Zondervan does appear to enjoy a certain measure of autonomy from its parent company. Further, the change appears to have been made before the acquisition; if you’ll notice the timeline, Zondervan was acquired by HarperCollins four years after the publication of the third revision of the NIV to not include this verse.

Further, it’s disingenuous to suggest that HarperCollins is some liberal outfit trying to destroy good conservative people. HarperCollins is itself owned by News Corp, which was founded by Rupert Murdoch as the publishing arm of the same company that runs Fox News. News Corp has been spun off from its parent company, but is still run by Murdoch, well known as a profoundly conservative man.

Finally, while Zondervan publishes the NIV in the United States, the version has other publishers worldwide. Biblica themselves, the translators, publish the Bible digitally, for instance.

The Right Question

I said above that this meme is insinuating the wrong question. What I meant by that is that we shouldn’t be asking “why were these omitted from the NIV (and ESV, and almost all other modern versions)?” but “Why were they added to the KJV?”

The fact is, in the 17th century when the KJV was being translated, they didn’t have manuscripts as reliable as we have now. The manuscripts which include these verses are hundreds of years older than the manuscripts which don’t, and we’ve only found those manuscripts in the last few hundred years of archaeology. The Textus Receptus, which was a Greek version of the New Testament used by the King James translators for the Authorized Version, was assembled and collated by the scholar Erasmus only about a hundred years before the KJV began translation. The documents from which it was sourced are themselves also not original, dating largely from the fourth and fifth centuries; and Erasmus’ published version was “adjusted” to more closely match the Latin Vulgate version.

In the nearly half-millennium since the translation of the King James version, archaeology has exploded as a field of study. We have more examples of the Word of God available to us than ever, and by and large, they all say the same thing. Further, the New Testament manuscripts and fragments we have access to now are, in some cases, less than a century separated from the life of Christ and, when taken in context as a whole along with the Textus Receptus, can be seen to represent Scripture, preserved by God and handed down throughout the ages.

Kept Pure In All Ages

Most confessions and creeds hold that the Bible is God-breathed and infallible in its original manuscripts; the Westminster Confession, to which my church and I hold, agrees. I would further assert that, just as none of us individually are the people of God, but all of us together are, the whole of Scripture has been preserved as a community of texts through which we see what God originally inspired the authors to write.

But the 1611 KJV was not an original manuscript; it has longevity, and it is valuable, but it is not infallible. It shouldn’t be considered the source or arbiter of textual criticism, and this meme makes a mistake on that point.

Most Christian Biblical scholars also believe that, while God hasn’t inspired any further Scripture, He does protect the Scripture he already wrote. This meme makes a further mistake there, in assuming that the publishers of the Bible are more powerful than the Author of it and can stymie His will.

In the end, it seems we just reckon with a simple choice: did a hyperconservative chief executive order a publishing company he didn’t own to make make a liberal change in a version they didn’t author to two Bible verses which don’t change doctrine in any appreciable way for no apparent or discernable reason, and then maintain that deception until some random person on the internet noticed? Or was it just a mistake in the manuscripts available in 1611 that we discovered in the 350 intervening years between the KJV and the NIV?

The bottom line is, you can trust your Bible in most widely-available modern versions. It’s been independently verified by people smarter than this random guy on the internet, and it’s been protected by the God who wrote it.